The Albanese government’s migration strategy released today commits to bringing net migration — that is, the net long-term and permanent movement of people into and out of Australia — to pre-pandemic levels by 2024-2025. That is down from the current level of around 500,000, with it steadily declining (375,000 in 2023-2024; 250,000 in 2024-2025; 255,000 in 2025-2026) until it reaches the 235,000 net migration assumption used in the two most recent intergenerational reports in 2026-2027.

Since World War II, Australian governments have always set targets for the number of permanent visas issued but that has been inadequate for at least a decade with strong levels of long-term temporary migration. Under the new strategy, the permanent migration and humanitarian programs are to remain largely unchanged but it is net migration that is to be reduced.

This is the first time any Australian government has said it wants to reduce net migration and may set a target for that, noting that earlier this year Treasurer Jim Chalmers described the Treasury’s forecasts for net migration as being neither targets nor policy. He said the government did not have direct control over net migration. That is true, but it does have very significant indirect control if it sets its mind to it.

The Treasurer’s comments were before it became obvious the blowout in net migration would become a politically charged issue — one the Opposition has been eager to exploit. That has changed everything. Getting net migration down to an acceptable level before the next election has become a priority to prevent an ugly immigration-based, dog-whistling election campaign.

The new migration strategy also states the government will take:

“Population planning” is a new term in the Albanese government’s vocabulary, one that it has eschewed to date. It was a term Scott Morrison happily threw around but for him, it didn’t mean much more than a political marketing tool.

Hopefully, the new commitment to reducing net migration, and to population planning, means the government will work with the states to set a long-term target for net migration and establish a framework for managing that. The management framework is critical to avoid the kind of blow-out that occurred in 2022-2023.

If the Albanese government follows through on these commitments and the Coalition also supports such an approach, that will represent a very significant shift in the way migration is managed in Australia.

Sadly, government talking points suggest it may be walking away from setting a long-term target for net migration.

Opposition spokesperson on immigration Dan Tehan has simply resorted to accusing the Albanese government of pursuing a “big Australia” strategy by stealth. He fails to mention that the Coalition’s 2019 Budget forecast Australia’s population at the end of 2022 would have been 500,000 more than it was. If Labor is pursuing a “big Australia” strategy, how would Tehan describe the Coalition’s approach?

This type of political game playing on this issue makes it even more important that the media ensure both major parties manage migration in a way that can assist with planning in all sorts of areas including housing, infrastructure, government service delivery and business management.

But is the media in Australia capable of pressing governments on the national interest rather than just barracking for one side (especially the Murdoch press)?

How did we get here?

The Albanese government inherited a set of COVID-era immigration policy settings that were designed to retain students and other temporary entrants already in Australia, and attract more very quickly when international borders re-opened, including a range of fee-free visa types, unlimited work rights for students, a new Agriculture Visa and so forth.

With an extraordinarily hot labour market in 2022, and pressure from the business community and the Coalition to further boost immigration, the government increased the permanent migration program to 195,000 and began clearing the massive onshore and offshore visa application backlogs the Coalition had allowed to build up.

Note massive backlogs create opportunities for the unscrupulous to exploit the visa system. They almost always represent bad practices and have to be dealt with. They could not continue to be ignored as Peter Dutton ignored them when he was Home Affairs Minister (and illegally so for partner visas).

By October and November 2022, it was clear net migration was booming, driven largely by students but also working holidaymakers and visitors extending their stay. It was at that point I thought the government would act to slow the net migration boom including by quickly tightening many of the COVID-era policy settings. That would have ensured net migration was kept well below the Treasury’s revised forecasts for net migration (400,000 in 22-23 and 315,000 in 2023-2024).

Surprisingly, the government did not start to act until mid-2023. (It may have been relying on the Treasury’s forecast of a sharp deterioration in the labour market to bring net migration down.) When the government did act, it did so in a very limited way.

In fact, it added to the boom by introducing even more generous temporary graduate visa provisions, providing a direct pathway to Australian citizenship for New Zealand citizens in Australia (which has attracted more New Zealand citizens to Australia), boosting poorly designed visas for Pacific Island nationals and for too long ignoring the resurgence in asylum applications after international borders re-opened.

Thankfully, the Albanese government did shut down National Party leader David Littleproud’s Agriculture Visa, which would have seen net migration grow even faster with turbo-charged levels of migrant worker exploitation and asylum applications. Littleproud had the wool pulled over his eyes on the Agriculture Visa by the National Farmers’ Federation.

Where to now?

For the 12 months to September 2023, net migration was around 500,000, a completely unprecedented and unplanned level. Notably, there have also been net migration blow-outs in the UK, Canada and New Zealand with these nations now acting to reduce net migration. To date, none of them have had a system for managing net migration.

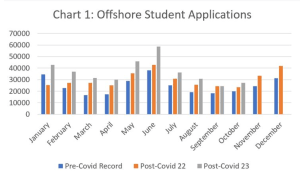

To reduce net migration to pre-pandemic levels by 2024-25, the migration strategy focuses almost entirely on further tightening policy on student and temporary graduate visas. That is understandable given students in 2022 contributed almost 60% to net migration.

However, there is no specific mention of tightening policy regarding visitors extending stay (around 18% of net migration in 2022) or for working holidaymakers (over 10% of net migration in 2022). For working holidaymakers, the government proposes to issue a discussion paper in early 2024. That means the current surge in working holidaymakers (an additional net 15,000 just in October) will continue in November and December.

If it wanted to tighten the working holidaymaker policy to limit the net migration boom, the government should have started the review of the working holidaymaker policy as soon as Dr Martin Parkinson recommended it at the start of 2023, not the start of 2024. There was no reason for the 12-month delay in issuing a discussion paper. That also applies to other visa-related discussion papers the government says it intends to release next year.

The migration strategy includes other measures to marginally tighten policy on employer-sponsored temporary entry (some of the measures will increase demand for this type of temporary entry) and the number of people on the special COVID visa should gradually decline, although what they will do when their visas expire remains uncertain. For many, lodging an asylum application to further delay departure may be their only remaining option.

The Federal government recently announced a $160 million package to start addressing the massive backlog of asylum applications that started under Peter Dutton. But as it had known of this problem since well before the 2022 Election, why did it take so long to act?

In addition to tightening of student visa policy that has already been announced, the migration strategy further proposes the following changes.

- Higher English language requirements from early 2024: this is sensible but the government will need to be vigilant to ensure English language testing providers do not dilute English language testing requirements (for example, one major provider now allows test takers to re-sit one element of the test they may have failed without having to re-sit the whole test). Increasing English language requirements should have been implemented much earlier in 2023.

- Shorter post-study work rights other than for regional Australia and for skills in demand: this is also sensible but raises the question why post-study work rights were made more generous on 1 July 2023 (perhaps from pressure from industry that should have been resisted).

- The introduction of a new “genuine student” requirement to replace the “genuine temporary entrant” requirement: this is also a sensible change but will depend on how the “genuine student” test is designed. If it is excessively subjective, it will suffer from many of the same problems as the “genuine temporary entrant” test.

- Prioritising students enrolled with low-risk providers over high-risk providers who would be subject to higher levels of scrutiny: another sensible development but it would be surprising if this wasn’t already happening given the increased offshore student visa refusal rates and slower processing that is already evident.

- Measures to reduce onshore student visa “hopping”: this is also sensible but if this is based largely on subjective criteria, it will soak up large amounts of visa processing resources and appeals, including pressure on immigration compliance for those refused an onshore student visa. The Albanese government has restored some of the Coalition’s cuts to immigration compliance but not nearly enough.

- $19 million for a student visa integrity unit to better address student visa fraud and work with the Australian Skills Quality Agency (ASQA) to deal with dodgy private VET providers: this is another sensible measure as it may help give ASQA a backbone.

It is good the Albanese government has not, as suggested by some, used “capping” tools to restrict student visas granted nor has it massively increased student visa application fees. Both are blunt and ill-equipped instruments that fail to understand the wider public interest objectives of student visa policy.

The key to tightening student visa policy is to reduce the offshore application rate using objective criteria that target high-performing students. If that does not decline and the government relies mainly on high refusal rates using subjective criteria and slow visa processing, net migration will not fall nearly as quickly as the government wants and the stock of students in Australia will continue to rise from its current record level of 672,782 at end October 2023, particularly in the March quarter of 2024.

To date, offshore student visa application rates continue to be unsustainably high.

A possible objective tool is to use national university or vocational college entrance exam results used in most of our source countries. There is no reason why it should be easier for an overseas student to get into a university or vocational college in Australia than it is to get into a top university or vocational college in their home country.

Another advantage of using national entrance exam results is that the Australian government can dial exam result requirements up or down as needed to give the government greater control over net migration.

Use of these national university entrance exam results would be strongly opposed by Australia’s international education industry as Australia struggles to attract high-performing students and the lobby groups know this. The Albanese government would need to stand up to the international education industry lobby groups on this issue.

To date, the government has not provided any publicly available analysis of the impact of each of its various measures to reduce net migration, including on application and grant rates for key visa categories. As usual, the public will only get the very top-line estimates produced by the Treasury in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook and a few additional scraps from the Treasury’s Centre for Population.

Hopefully, some more detailed and robust analysis exists but I fear it may not. Despite all the fanfare, Josh Frydenberg’s Centre for Population has few relevant skills in this area and Dutton and Mike Pezzullo ensured immigration research and statistics were a low priority in the Department of Home Affairs.

If no detailed and robust analysis supports the migration strategy objective of getting net migration down to pre-pandemic levels by 2024-25, the Albanese government may continue to fly blind on this issue. This would represent a high-risk approach given how keen the Opposition will be to use high net migration as an election issue.

In the meantime, the government will continue to be hammered on this issue during 2024 as the ABS will release updates of its estimates of net migration in 2023 and early 2024 at very high levels throughout 2024.

This article is reproduced with permission from Independent Australia.

READ MORE: